Win Diesel: A Proposal for Reducing Turkish Diesel Prices

Global diesel and gasoline margins (the difference between gasoline & diesel and crude oil prices) skyrocketed since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine War in February 2022. A rough explanation of why this happened is, Europe has been buying a lot of its diesel from Russia while neglecting its crude oil refining capacity for basically decades, and with the war, this structure came crumbling down, at least the markets priced it that way. This pushed the diesel and gasoline prices up in Europe and global producers rushed to profit from these large margins and export their products to Europe and that in turn caused price spillovers to the US and other places.

Source: Bloomberg, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. (Last Observation: October 27, 2022)

The problem for Turkey is, it determines its domestic oil product prices via indexation to two European contracts: Platts European Market Scan CIF MED Genoa/Lavera Gasoline and Diesel. So, the domestic gasoline and diesel prices skyrocketed in Turkey as well.

Source: Galata Chronicles’ calculations, EMRA, Bloomberg

In this article, we will argue that the current conditions require severing that indexation relationship and insulating the Turkish economy from what are basically the results of European mistakes in its energy policy while making sure that some of the discounts Turkey gets in its Russian oil imports that currently accrue in their entirety to Turkish refineries and distributors are reflected in the pump price consumers pay and propose a two-step plan for doing so.

Why?

Normally we would be inclined to adhere to the dictum “the solution to higher prices is higher prices”. If an unusual price formation goes on for a while, the natural expectation would be that that period of sustained extraordinary profits would beget investments in that industry and that would drive the prices down. In this case, however, there are a few reasons why this reasoning will not work:

1. Oil refining investments have remarkably high fixed costs and investment lead-times. This essentially means that if a price anomaly is not forecast to last beyond, say, 4-5 years, it would not be enough to entice people to build refineries because it would not be worth it. And the current crack spreads do not forecast the current anomaly to last that long. (We do realize futures contracts are not exactly forecasts, oil nerds, calm down. You get our broad point.)

Source: Bloomberg

2. The current predicament is more or less entirely because of the Russia-Ukraine War, which is, by its very nature, unpredictable. So, any refinery investment, either in Turkey or in Europe, the epicenter of this issue, predicated on the possibility of a never-ending war, and never-coming-back-Russian-supply-for-Europe would be particularly ill-advised and would deserve a much higher required return given the risk. So, it would not be an extreme stretch to say that such investments, especially in Europe, won’t be made by the private sector. That leaves governments but we have a hard time believing that European governments will form state-owned enterprises to build refineries in a continent where the energy policy is so unrealistic or non-existent that the absolute necessity of nuclear energy is still very much overlooked and controversial. So, the structural problem seems to be here to stay.

3. Another sensible counterargument would be that lower gasoline and diesel prices would encourage more consumption which would deepen oil dependency and slow down the energy transition. The part about oil dependency is likely correct. The problem is, there is still no viable mass-market alternative that would be strengthened by high oil prices right now in Turkey. Therefore, high diesel prices are a huge net negative, dynamically speaking. There will be alternatives in a couple of years, and that is another reason why refinery investments are not happening globally and locally, but it is not here yet. That’s why an intervention that will remain in place until then is in order.

Why now?

Because the European Union embargo on Russian crude oil is scheduled to start on December 5 and the embargo on Russian oil products will be implemented as of February 5, 2023. This will not only create a scramble for oil and products in Europe, but it will also increase, or at least sustain the diesel crack spreads. If that happens, President Biden might also ban oil product exports to Europe, to prevent a spillover into the US that would obliterate his re-election chances and strongly dent the support for Democrats, and that would pretty much cause European prices to skyrocket immediately. (Though that is admittedly the nuclear option and seems unlikely for now, some reports suggest that Biden previously considered that and was persuaded otherwise by some of his aides because it would quite certainly demolish the transatlantic relationship.)

Therefore, as a country that currently does and will continue to buy Russian crude oil and oil products, Turkey subjecting itself to such an ordeal willingly would be a significantly bad decision and would basically mean paying for Europe’s past sins.

(Geopolitics Interlude: One possible question is, wouldn’t the EU and the US react to Turkey continuing to buy Russian crude and products after the embargo, and the answer is a forceful “no”. The main aim of the price caps and the embargoes is to decrease the price of oil but to keep the flow intact. Otherwise, global oil prices would skyrocket, and the latest OPEC+ production cut made sure of that. In fact, by buying more Russian crude on the cheap, Turkey, India, China, and many others would be doing a favor to the US and the EU because it would mean more “elsewhere crude” available for them. And the ongoing discussions about the price cap involve a price level that is quite close to the current Urals prices anyway.)

What?

The current excessive domestic diesel price issue has two parts, and we’ll propose a solution in two steps. The first step will involve dealing with Russian oil-related pricing issues:

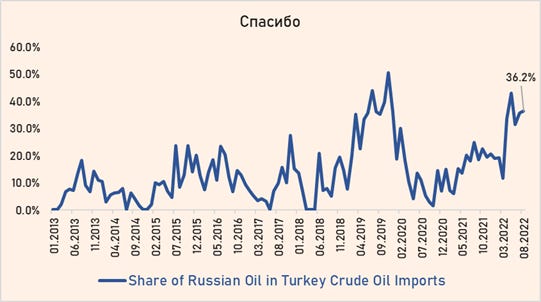

Turkish refineries (TUPRAS and STAR) benefit from the Urals discount, and Turkish distributors import Russian diesel relatively cheaply, but the entirety of said benefits accrue to the importers and none to the end-users of the products. Turkey currently satisfies roughly 35 percent of its crude oil needs from Russia and Russia’s share in Turkish diesel imports is around 45-50 percent. Roughly two-thirds of Turkish domestic diesel consumption comes from local refineries and the rest is from direct imports.

Source: EMRA, Eurostat, Galata Chronicles’ calculations

Currently, Russian crude oil is traded with a roughly 20-25 dollar discount to Dated Brent, and there seems to be a similar discount for oil products as well. That’s why Turkey is able to spend significantly less than it would have if it did not receive Russian supply, and as we said, this benefit accrues to the importers in full right now. Our calculations indicate that if the Russian crude oil and product discounts were fully reflected in the final tax-free prices, that would result in a 22 percent, or 3.55 lira decrease in the current diesel prices.

Our proposal’s first step is to start with a 75 percent Platts European Market Scan CIF MED Genoa/Lavera + 25 percent Russian diesel indexation. The reason why we didn’t immediately start with a full cost-plus type indexation that would result in a roughly 40 percent weight for Russian oil is that doing so would:

1. Remove the incentive of refineries and importer-distributors to buy Russian crude oil and products and Turkey needs to buy more, not less from them.

2. Because of the upcoming EU embargo, it will be impossible to import Russian oil using EU tankers, and that will likely cause some significant fluctuations in freight prices.

The actual rate can be adjusted more accurately by the regulators who are naturally more knowledgeable about the ongoing costs involved in buying from Russia.

The reason why we propose a two-step process is that refineries have a significant amount of crack spread hedges for the next two quarters, and it would significantly hurt refineries to force them to unwind said hedges immediately. And with the first step, we would be leaving the crack spreads accruing to the refineries largely intact so that their hedges would not blow up, and only their crude oil hedges would be affected, but the likely result would be that they will profit from that because of the relatively recent decline in the Urals margins. From TUPRAS’ latest quarterly report:

“As of 30 June 2022, and 31 December 2021, commodity derivative transactions consist of average refinery crack margin fixing transactions and crude oil sale and purchase transactions. Average refinery crack margin fixing transactions have been executed for, gasoline stocks of 2,268 thousand barrels, jet fuel stocks of 1,301 thousand barrels, diesel stocks of 4,114 thousand barrels, and fuel oil stocks of 1,108 thousand barrels for the third quarter of 2022. And gasoline stocks of 1,253 thousand, jet fuel stocks of 724 thousand, diesel stocks of 2,680 thousand, and fuel oil stocks of 629 thousand for the fourth quarter of 2022 (31 December 2021: Gasoline stocks of 551 thousand barrels, jet fuel stocks of 214 thousand barrels, diesel stocks of 1,061 thousand barrels and fuel oil stocks of 214 thousand barrels for the first quarter of 2022).”

One key thing about this first step is that the public should not know about the existence of a second step or the counterparties in those hedges would fleece the Turkish hedgers. (Yes, we do realize the irony in that sentence, but we have to make our proposal heard in some way and we, unfortunately, don’t have the cell phone numbers of the regulators.)

The second step involves enforcing a constant crack spread. We think a valuable benchmark in this regard is the trajectory of the diesel crack spreads between 2015 and February 2020 because that period was the new elevated normal after the oil price crash in 2014-2015. The average diesel crack spread then was 22.43%. But the refinery input prices like natural gas etc. increased a lot in the case of Turkey as well, so to adjust for that we add 2 standard deviations on top of that average and arrive at 33.3%. (Once again, the exact numbers are up to the regulators who are privy to the exact cost dynamics of the refineries.) If this is done, there’ll be an additional 2.35 Lira decline in the tax-free diesel price, and with the gain provided by the first step, we think a cut of 4.5-5.0 Liras is possible in the tax-included price, which would pretty much erase the price differential between diesel and gasoline.

We think two additional elements are necessary to prevent any hiccups:

1. Re-exports of diesel by the distributors are fine and should just be registered.

2. Exports of the refineries should be capped at their current levels.

We would love to hear from oil market professionals as to why our proposal would not work so that we can revise our points and plug those holes. The key thing is, Turkey needs to be shielded from the impact of the explosion in European diesel prices that will likely be with us for some time, one way or another.