This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things: Turkish Housing Market | Either Appeal to the Rich or the Poor, Not in Between!

Section I: This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things: Turkish Housing Market

Intellectual Honesty Disclaimer: A significant number of the best economics and finance stories are like this Escher painting: All stairs go both up and down, everything causes everything and nothing is linear. The story below is going to be no exception. That’s why, to spare you the boredom of having to read a bunch of intellectually more honest but weasel-y words like “is associated with”, “co-move”, “more likely than not”, we’ll be a bit more “daily-life” when talking about various causes and effects. Just know that in almost all conclusions that will be drawn here, the chain of causality might as well work the other way around.

This is going to read like a tragedy. In some respects, it certainly is. And like all good tragedies, we’ll give you the ending in the beginning and it won’t make a difference because like all good tragedies, it’s not the ending that makes the whole story worthwhile. It’s how the story got to that ending.

This will also, almost completely, be a macro story. There are of course important differences between the situations in different cities, but when we ran a Principal Component Analysis on all the province-level house price series, the first principal component explained a whopping 82.2% of the total variation in the dataset. (For the normal people, this meant that the macro story was by far the most important). Perhaps, one exception is the case of Istanbul, and that’s because when we ran a Vector Autoregression, lagged house price changes in Istanbul turned out to be statistically significantly impactful for 16 other regions. (Istanbul price leads, other regions’ prices follow)

Epilogue:

Residential real estate prices in Turkey had the largest inflation-adjusted increase in the world for the last couple of years, bar none.

Source: TurkStat, CBRT, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: July 2022.

While homeowners are probably jubilant about this fact, this spectacular rise has and will have grave consequences for a significant part of the society, unless the correct lessons are drawn from this weird episode.

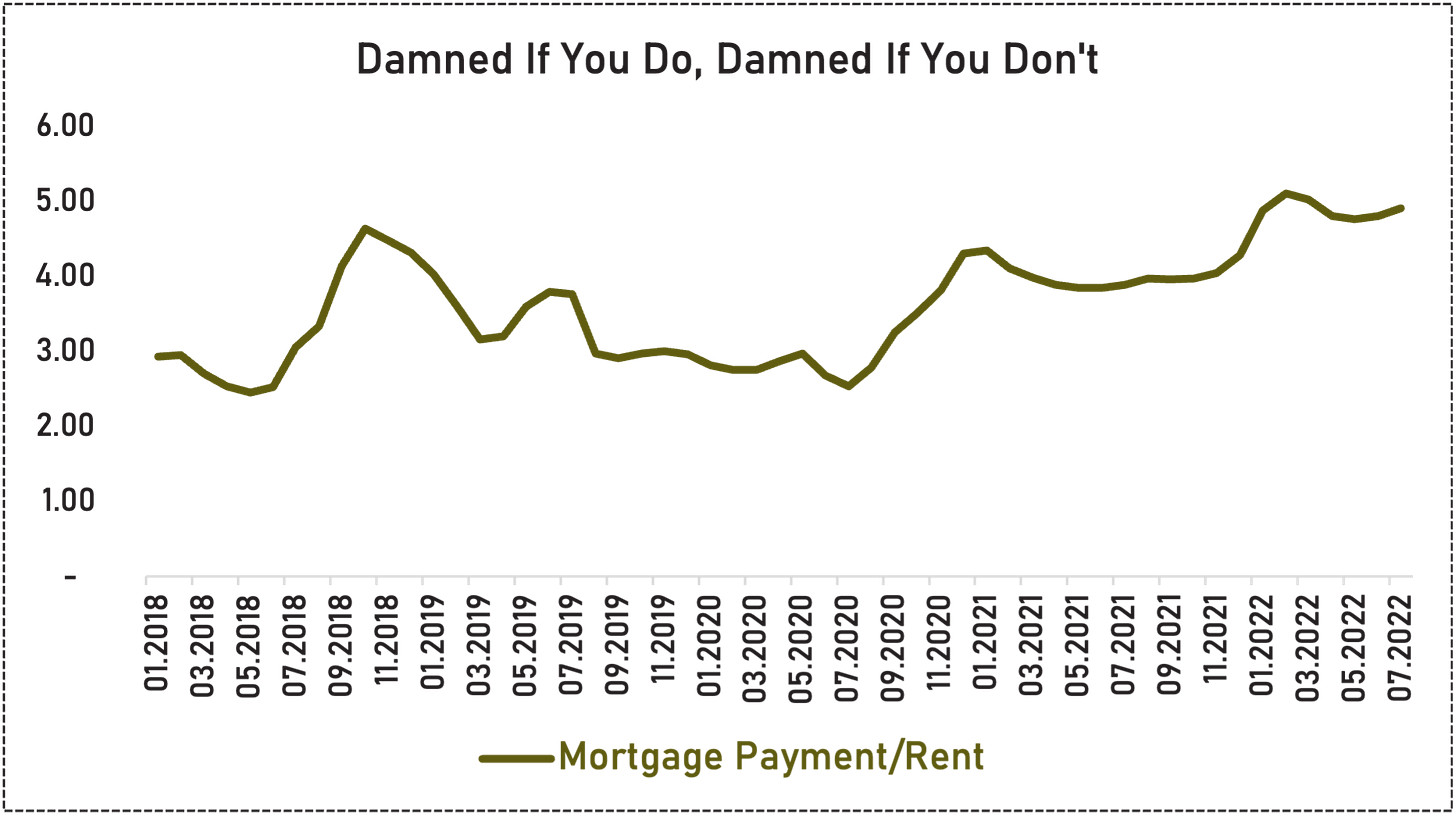

One immediate consequence is, at least for now, buying a house is impossible for a group of people the number of which is larger than some European countries. The chart below is the ratio of the monthly mortgage payment 90% LTV for a 100m2 home to the monthly minimum wage. That last drop in the chart was because of a significant minimum wage hike done in July. As it is quite apparent, it helped, but there is a long way to go before a home is as affordable as it was.

Source: TurkStat, CBRT, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: July 2022.

But the more important consequence for Turkey’s future is, it will take a lot of time and effort to persuade Turkish people to invest in higher risk / higher return assets that will actually raise the productivity of the country.

We here at Galata Chronicles are avid proponents of Georgism and we think rent extraction from real estate is one of the main reasons behind Turkey having a difficult time creating a proper bourgeoisie that supports innovation instead of stifling it and has the requisite risk appetite to support the development of equity markets, which would open a separate avenue of financing productive investments, instead of wanting excess real rates from riskless investments.

Turkey needs to move away from this vicious cycle:

Firms and households invest in real estate. Real estate prices increase. This pattern repeats itself for a while so people start to buy real estate for capital appreciation rather than income. This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Banks start to prefer real estate collateral in commercial loans because they deem everything else more risky. (Utter the words “cash collateral” to a Turkish businessman and watch yourself getting laughed out of the room. And “equity collateral” might as well be a movie starring Tom Cruise for a lot of Turkish bankers) This means two things:

1. Real-estate-poor firms have an extremely hard time accessing bank loans. (We’d strongly argue that there is a negative correlation between a firm’s real estate ownership and its productivity, so this effectively means you created a banking sector that discriminates against innovation and sound economic practices. Since Turkey has an extremely bank-dominated finance sector, you can figure out how this goes)

2. Firms that would otherwise not load up on real estate will now do so to be able to receive bank loans. And that means, you guessed it, more demand for real estate that has zero interest in the use value of the darn thing.

Rinse and repeat.

Don’t get us wrong, we like bubbles and folks making money as much as the next guy, but we’d just strongly prefer that it doesn’t happen in something that crucially affects the livelihoods of millions of people who did nothing to deserve the consequences.

First Act

For the Internet Explorer users among us: Turkey had an exchange rate crisis in 2018.

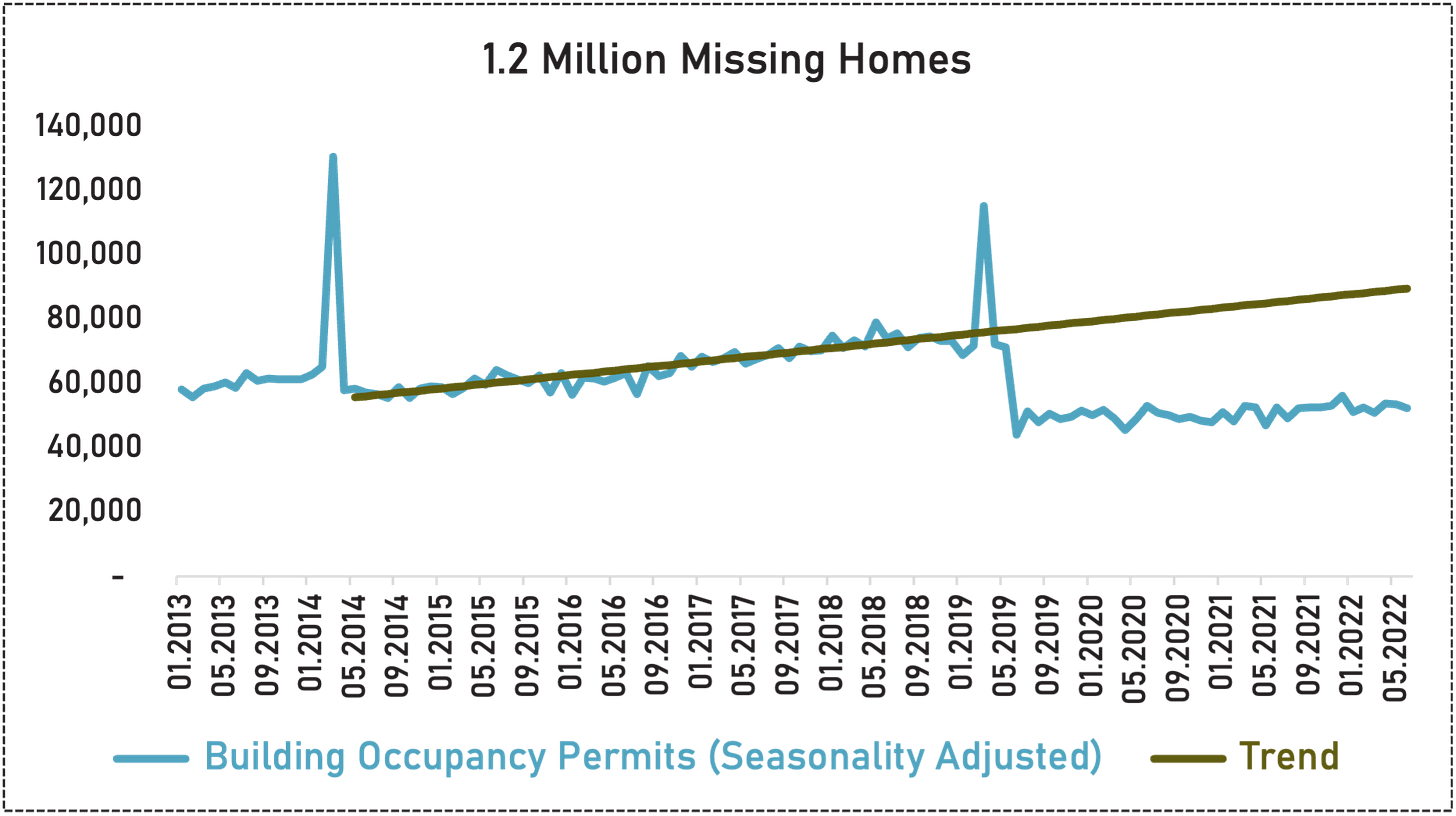

It caused A LOT of things, but a significant one was that it basically stopped real estate construction, and no, I’m not exaggerating. The industry had already been hurt by the slowdown in demand in the last couple of years by that point, but the crisis and the extraordinary rate hikes that were needed to put a lid on it were the needle that broke the camel’s back. The chart below shows the seasonality-adjusted number of occupancy permits issued per month and the trend line based on the way things were between 2014 and 2018. A lot of factors go into coming up with an accurate picture of the subsequent shortfall, but this might at least provide a ballpark: The cumulative difference between the trend and the reality is 1.2 million houses. That’s almost as many as an entire year’s home sales, and triple the number of average annual new home sales.

Source: TurkStat, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: June 2022.

We think that trend line is still more or less appropriate for two reasons:

1. Employment is roughly back to its long-run trend.

Source: TurkStat. Last Observation: June 2022.

2. The home-ownership rate is down by 3 percentage points from its long-run average of 61%, and the ratio of tenants is, therefore up by 3 pp.

Long story short, what set the stage for the subsequent events was that the flow of housing supply slowed down to a trickle.

Also in 2018, the government implemented a policy that will be relevant down the line, that was somewhat sensible at first, then outlived its usefulness and lastly, became something inexplicable: Foreigners who invest a specified amount in Turkey and keep it in for some time would be given a citizenship, and real estate was one of the investment possibilities listed. We said somewhat sensible, because remember, at the time there was a lot of unsold homes, the domestic market was stuck so letting foreigners buy a part of the stock probably seemed like a low downside, high upside thing to do. What made foreign purchases particularly toxic in terms of price impact was that they were price-insensitive, since the primary purpose was to exceed the minimum investment threshold, which was initially 250.000 USD and then was increased to 400.000 USD.

Source: TurkStat, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: August 2022.

Second Act: A Series of Unfortunate Events and Unforced Errors

Things were largely normal until 2020 and residential real estate prices even declined in real terms during 2019. 3 distinct shocks basically determined the following stratospheric rise in prices:

1. Cheap Mortgage Loan Packages

In June 2020, the state-owned banks announced a cheap mortgage loan package with the lowest interest rates in the Republic’s history. Again, quite fitting for a tragedy, this one was also marked by good intentions. There was still a significant amount of housing stock, the pandemic was wreaking havoc and the economy was not OK.

The problem is, and this will come as no surprise for anyone with a modicum of market-making knowledge, the market immediately and completely adjusted the house prices up to almost fully compensate for the cheapness induced by the mortgage package. In the charts below from BETAM (to which we all owe a debt of gratitude for their amazing work on the housing market, using sahibinden.com data) you can see the impact of this and the subsequent cheap loan episodes. They significantly pushed up the marginal demand in a very short time and given the declining supply, the result was a remarkable rise in prices.

Chart: The ratio of the number of houses sold in Turkey to the number of ads for sale (%)

Source: sahibinden.com, Betam. Last Observation: August 2022.

2. Rent impact

Both the declining rentals supply and the impact of the pandemic caused a significant amount of turmoil in rents. The first spike in student mobility after the pandemic occurred in the summer and the fall of 2021, and this coincided with the pent-up demand from government employees who wanted to move elsewhere but couldn’t during the pandemic.

Chart: The number of rental ads and the number of rented properties (right) (Thousands)

Kaynak: sahibinden.com, Betam. Last Observation: August 2022.

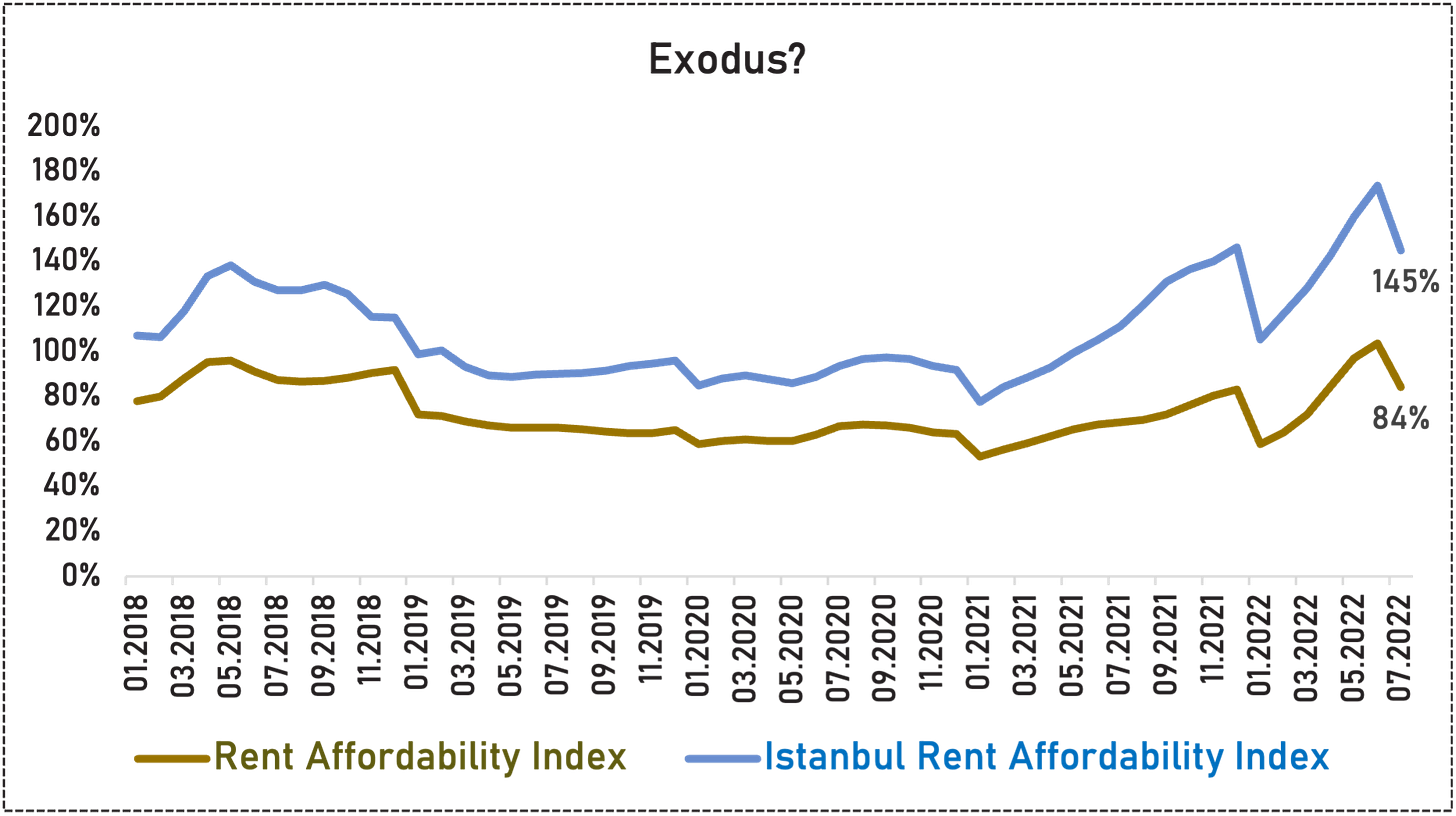

This meant that an unusual spike in rental demand that couldn’t be met by the marginal supply. The quick rise in rents also meant that people who would normally want to move, couldn’t because they were priced out of the market, so the supply of rental properties declined extraordinarily and never recovered. This further pushed the rents up. Rinse and repeat. The chart below shows the ratio of average rents to the minimum wage in Istanbul and in Turkey.

Source: TurkStat, Endeksa.com, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: July 2022.

3. Ballooning construction costs

Construction industry basically uses 2 inputs: Metals and minerals, and labor.

Source: OECD Input-Output Tables, Galata Chronicles’ calculations

The prices of the former skyrocketed both globally as a result of the pandemic, and locally as a result of the significant decline in Lira. And the latter’s cost rose substantially as a result of minimum wage hikes in the beginning and the middle of the year. Since the replacement cost is one of the key metrics in housing valuation, this situation provided a third leg of support to real estate prices.

Source: TurkStat, CBRT, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: July 2022.

Where do we go from here?

The best case scenario seems to be stagnant nominal prices and rent and declining real ones. Since costs, rents and prices reinforce each other. This outcome depends on a multi-pronged approach.

The social housing project announced recently that will consist of the construction of 500 thousand houses, 50 thousand commercial property and the sale of 250 thousand pieces of land sounds like a promising start. We care very little if this is an election investment or not. It is SORELY needed, period. We wholeheartedly hope that the entire project comes to fruition. The housing market is still frothy in relative terms.

Source: CBRT, Endeksa.com, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: July 2022.

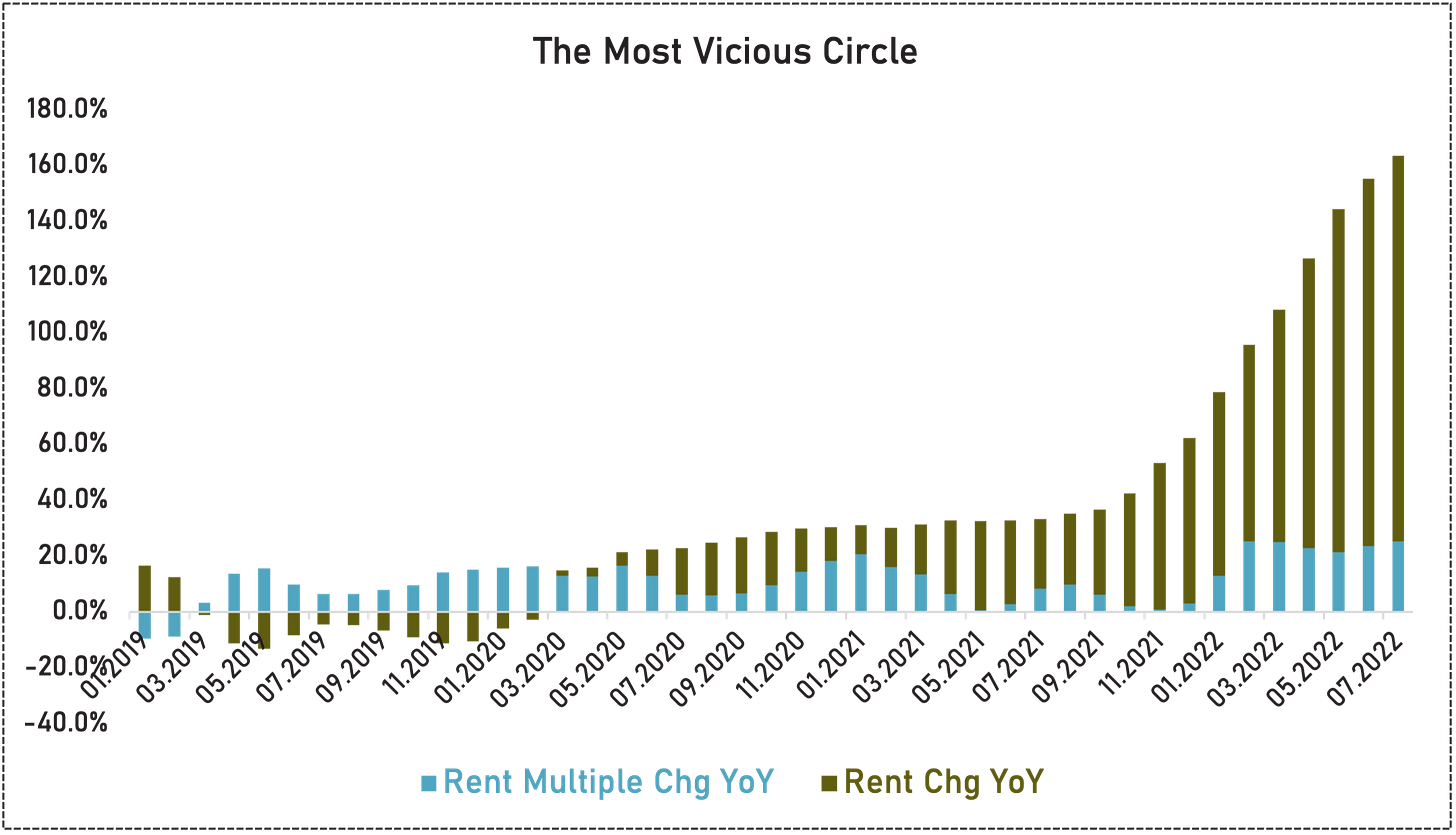

However, these houses won’t come online in the next year or two so some more urgent solutions are required, especially when it comes to the rental market, since multiple expansion is a relatively small piece of the puzzle and without some additional rentals supply, this bad equilibrium will perpetuate itself. The chart below decomposes the house prices into two components: Rent multiple expansion and rent increases.

Source: TurkStat, CBRT, Endeksa.com, Galata Chronicles’ calculations. Last Observation: July 2022.

So we think these three solutions would provide some respite:

1. Sales to foreigners should be stopped until fresh supply comes online. This should be extremely easy to do. People can invest in funds, stocks, bonds, bank deposits.

2. The real estate tax (council tax in the case of the UK) rates should be jacked up immensely to ensure that empty homes are rented as soon as possible. The rates should be high enough to compensate for the possibility of gaming the system.

3. Mortgage lending to people who already have a home should be prohibited, again, until fresh supply comes online. The usual reservation regarding this proposal is that people will game the system by transferring their properties to family and associates and to that we say, we’d like to see the try. First, they’ll pay title fees. Second, Turkey has the second lowest interpersonal trust among OECD countries after Chile, according to the World Values Survey, so the courtrooms will be filled with hilarious grievances as a result of attempts to game the system.

Even if these things are implemented, success is not guaranteed because the costs, at least labor costs will keep rising, as a result of the probable large minimum wage hike at the end of this year, and this will support prices in the short-run. The happening offers a silver-lining in that the result will be nominally higher but relatively more affordable prices.

Section II: Either Appeal to the Rich or the Poor, Not in Between!

In Turkey, the disposable income of households decreased significantly this year. In the CPI basket, the weights of food and transportation were the biggest ones (announced at the start of the year by TURKSTAT based on the household budget survey). These two categories steadily increased since January and further increased their weights in the basket (food: +54.10%; transportation: +54.18%). The demand in these categories is strictly inelastic. Except for alcoholic beverages and tobacco (+54.73%), these are the largest increases in the basket. As a result, the inflation in these categories decreased the disposable income of many people (many wage laborers) and made it harder to meet other needs. What does it mean for us (i.e., for investors)? What to expect for the rest of the year in terms of sectoral outlook?

The companies that already target lower-income people have relative advantages to sustain and grow their revenues (for defensive sectors, it is much more advantageous). These companies do not immediately need to adjust their branding strategy because they have already a proper customer base and many people will move towards them because of decreasing disposable income. On the other hand, luxury companies that already target higher-income people have the same advantages because the upper-income class (have many valuable assets regardless of their wages) increased its wealth due to the rapid increase in the value of the assets they hold (their FX deposits, real estate, etc.). Furthermore, because of the weaker TRY, interest for inbound tourism by foreigners is on the rise. Some luxury companies capture it. For example, the CEO of DESA stated that the share of retail sales to foreigners in its stores exceeded the share of locals. It should be noted that the fluctuation in the number of tourists can have a huge impact on these companies (although the expectation for this winter is quite positive).

However, for the companies between these two categories, things are a bit complicated. Especially in the middle and upper end of the middle segment, some companies must choose between raising prices or lowering quality. Strong price increases may cut consumer demand but may make it difficult to attract customers from the upper segments due to the previous brand image (for consumer cyclical sectors, it is more difficult). Another option is to reduce the quality. It will mean that the brand image that the company has created so far will be damaged.

Under these circumstances, some of our perspectives are the following:

- The companies that target lower-income people have the upper hand.

Examples: Food retail stores (like BIMAS, SOKM), LCWaikiki (not publicly traded), etc.

- The companies that target higher-income people or capture tourists’ interest have the upper hand.

Examples: VAKKO, DESA, OZKGY, DOAS, etc.

- The appetite for buying durable goods drastically declined with low disposable income. Moreover, the outlook in the export markets of Turkey is not positive. It is negative for white goods manufacturers such as VESBE and ARCLK, and furniture companies such as YATAS, and DGNMO (but the exports are more positive for the furniture sector). For automotive and automotive supplier sectors, those who only work for OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) are riskier due to the global demand slowdown for new vehicles. Long-term agreements with OEMs can pose difficulties in reflecting costs. However, companies that also sell products to the aftermarket can survive this turbulent period with less damage. EGEEN produces axles and axle parts for OEMs. GOODY sells its products both to OEMs and the aftermarket. As of the first half of 2022, based on the quantity, the share of the aftermarket sales in total is 41 percent, which limits downside risks for the company to some extent. Evidently, in the first half of the year, based on the quantity, while OEM sales increased just 4 percent annually, the aftermarket segment increased 57 percent.

- Despite the decreasing disposable income, we can expect the small appliances sector to be less affected by the slowdown in economic activity as it is less cyclical compared to the white goods sector. However, we should not forget that there is a demand that has been brought forward during the pandemic period. On a revenue basis, almost half of the small household appliances sector consists of the vacuum cleaner segment. The reason is that the selling price per unit is higher than other small appliances. Considering the rapid growth of the vacuum cleaner segment, companies that do not yet have a diverse product range in this segment are at a great disadvantage. At the end of 2021, ARZUM's share in the vacuum cleaner market was 2.1 percent.

- The companies which have “masstige” products can absorb the pressure more easily because their customer base is diverse in terms of economic well-being.

Examples: MAVI.

- Cyclical companies that have less-cyclical products have advantages to maintain their revenues.

Examples: CIMSA (the company produces white cement, in addition to grey cement, and the global white cement consumption is relatively stable compared to overall cement sector cyclicality).

Of course, the categorization is subjective and reflects our research.

In the coming years, if inflation cannot be tamed significantly, we predict that more companies will create new brands that target different economic classes, as in the case of YATAS and BIMAS. YATAS created Enza Home for the upper classes, Divanev for the lower classes. BIMAS created FILE for the upper classes.

In Turkey, consumption is one type of investment for a while because of high inflation. For the rest of the year, we expect that consumer demand will be clustered in some sectors and companies. Companies are likely to appeal to either the rich or the poor this year, not in between. In 2023, wage increases will eat a chunk of these effects. Last but not least, if the inflation in food and transportation starts to decrease, its effect will be multiplied because of their de-facto high weights in the basket now.

Disclaimer:

The articles on this website are for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

estate tax to fuel up rentals so not sure if it helps