THE OG ORIGINAL SIN

In Christianity, there is this concept of the original sin. A sin that humanity is born with, a sin that is quite ingrained in the very existence of humankind, a sin one can’t be absolved of. Finding this concept quite fitting for the developmental struggles of many nations, some pretty smart folks dubbed the inability of so many emerging market governments to borrow in their own currencies “the original sin”, as this was quite often the precise cause behind so many emerging market crises, manifesting themselves in various forms like banking crises, the balance of payments crises, governments becoming insolvent, asset price crashes or all or some of these all at once. Because if the majority of a country’s debt is denominated in a currency other than the nation’s own currency, whenever holders of that country’s debt decided not to hold it anymore, one got into deep trouble one couldn’t get out of by inflating the debt away, the reasoning went.

Well, it turns out, it wasn’t exactly the denomination of the debt per se, but the nationality of the holders of said debt, so came the “Original Sin Redux”, coined by Hyun Shin of the BIS, because if foreigners are the holders of your debt, whenever they decide to, well, not do that anymore, you were, once again in trouble (unless you decide to impose capital-flow-management measures, but if you utter the C-word anywhere near your retired-from-IMF friends, they will vanish into thin air, so be careful).

“The power of capital flow management compels you”

(We’re not even remotely doing justice to this vast literature in these two short paragraphs, so please read for yourself as well.)

Now, anybody with a cursory understanding of or interest in the Turkish economy knows that one major issue it has is that it cannot produce the vast majority of its energy, so it imports it. In this article, we will argue that this is not just another problem but actually, the OG original sin of Turkey so much so that it makes it look like the debt denomination and ownership issues mentioned above are more your run-of-the-mill, garden variety sins, like kicking cats or something.

Why? Because being so import dependent on energy, along with dollarization, collapses inflation-targeting into FX-targeting, and that is neither healthy nor sustainable in political economy terms, which renders the monetary policy non-credible in the long run.

Let’s go back to the beginning of the issue (not the actual beginning, we’re not geologists). In the late 90s and early 2000s, one problem Turkey had was that it wanted to grow, but it did not have the requisite energy production or potential to do so. Several major rivers were already dammed, it did not have particularly high coal reserves or production, and what it had was not good coal anyway (not high-calorie). So, the natural energy source of choice was natural gas, and new long-term contracts were signed with Russia and Iran.

Source: BP, Galata Chronicles’ calculations

(Turkey also had a major air pollution issue so it also chose natural gas over coal and wood in household heating.)

Source: BP, Galata Chronicles’ calculations

After the 2001 crisis, facing an economy with remarkably high inflation and deposit dollarization rates, the policymakers at the time implemented a policy of high interest rates and free capital flows, and freely floating exchange rates (in this article, we will take this structure as given, we don’t want this piece to turn into something about dollarization, as it invariably does in our daily lives).

We will postulate something that should be kept in mind in literally every single discussion about Turkey: Growth is always non-negotiable. Growth is always non-negotiable if an economy has to create roughly a million jobs each year just to keep the unemployment rate constant. Any statement that involves the word “should” that fails to take this into account is pure nonsense and has no place in any serious policy discussion. Nor does any policy advice that would result in perpetual output gaps.

So, what do we have now?

1. A central bank that offers real rates way above its emerging market peers throughout the 2000s, to fight against inflation and dollarization.

2. An economy that satisfies its energy demand with imported commodities.

3. A government that naturally prioritizes growth.

The natural consequence of these three facts is that the economy accumulates FX liabilities so fast that heads would spin. Because (1) makes sure that any TL borrowing is prohibitively expensive, and because it provides currency appreciation and stability, USD borrowing is too cheap for corporates. (2) ensures that (1) is always in place because if the energy prices are rising globally, an inflation-targeting central bank will have to offer positive real rates and preferably more positive than what its peers offer, as this is a supply shock, and the FX channel is the ONLY way CBRT could affect anything. And (3) ensures that FX borrowing keeps going.

Why did we say the FX channel was the ONLY way? Excellent question.

Because CBRT rate hikes actually relaxed the domestic financial conditions for two reasons:

1. Partially because of (1), there was no domestic demand channel to speak of, as TL borrowing for corporates was not an option, and because it decreased the CDS of the country and made FX borrowing cheaper. (We frequently say Turkish banks stopped being Money Market Funds and turned into actual banks only after the global financial crisis)

2. Because rate hikes strengthened Lira, so in effect it, let alone decrease, it increased domestic demand. So, rate hikes actually increased the current account deficit.

Shocking, right?

The obvious question at this point is “so what if inflation-targeting by CBRT has to effectively be FX-targeting, what’s so bad about it?” Again, excellent question.

What’s so bad about it is that it caused:

1. Premature deindustrialization, because importing stuff got way cheaper over time.

2. Way too much FX debt (Well, hello the original sin), which blew up the Turkish economy in 2018 and we’re still in the FX deleveraging mode four years after the shock occurred.

Another fair question would be, “so you told us about half of the picture where energy prices are rising, but it seems that CBRT inflation-targeting would not collapse into FX-targeting when global energy prices actually decrease”.

Well, you wish. Unfortunately, in the olden days, before the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War, there was this thing called the inverse correlation between energy/oil prices and the US Dollar. So, when oil prices crashed, you’d have:

1. Decreasing global trade, which affects Turkey more than its peers, because the goods it exports are way more elastic than the goods it imports.

2. Depreciation pressure in Lira, which, if unchecked, might kick-start, you guessed it, dollarization, and increase inflation.

So once again, CBRT had to target the FX rate.

[Honesty Interlude: At this point, we can’t escape the corollary of this line of reasoning: The inflation-targeting experiment that started in 2001 was horribly premature. HOWEVER, this does not mean that if we were given the same information set the policy-makers at the time had, we wouldn’t make the same choices. We ABSOLUTELY would. Now and in the future, we will always be careful about this distinction when we talk about past policies and there’ll be some choices we hate unconditionally, like Prime Minister Demirel’s choice to lower the retirement age, and some we find reasonable and wrong. The story we talked about today firmly belongs in the latter camp.]

The story unfortunately doesn’t end there. We frequently tempted fate before the pandemic by saying “what could be worse?” and we found out: USD and energy/oil being POSITIVELY correlated. In the chart below, you can see the impact of skyrocketing gas and oil prices on the Turkish energy imports. (The data below is not actually publicly available, but our estimations based on some econometric magic.)

Source: Galata Chronicles’ calculations

This article got way too dark for our taste, so we would like to finish with a ray of hope:

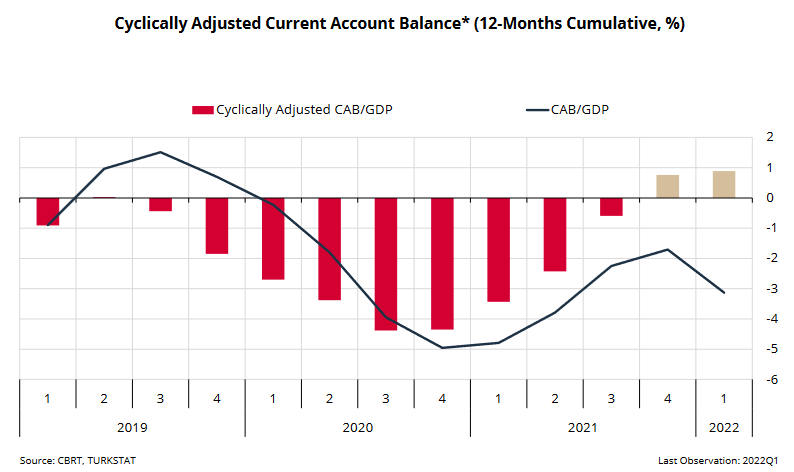

Turkey now has a cyclically adjusted current account surplus with constant prices. This means, once and if this nightmarish hellscape of never-ending global energy crises actually ends, Turkey will be on the cusp of absolution.

This was the first of four articles we will be publishing on the energy issue, if nothing more urgent and important arises in the meantime, which is a big if. Today’s piece was meant to answer the question “just why do you care so much about Turkey being an energy importer”, and we will be delving more deeply into the nuts and bolts of this topic in our upcoming articles.

Regarding current account surplus, isn't Turkey net importer when it comes to "intermediate goods" and "capital goods" ?

How come Turkey can result positive CAB after energy prices normalize ? ( Let's not forget high price elasticity of its exports)

What is the best email to reach you at?