From Everest to Mount Ararat: Turkey CPI Analysis

If there was an economics-themed Family Feud and we asked a hundred people off the street what the biggest issue plaguing the Turkish economy right now was, you would definitely bring the round to your team by saying “Inflation” and the only question would be how fast you hit the button to say it. We at Galata Chronicles love to analyze Turkey's CPI deeply and by deeply we mean at 4–5-digit NACE code levels but let’s admit it right out of the gate, such analyses wouldn’t exactly break readership records if we published it. (This would probably appeal to bank treasury folks who are knee-deep in CPI-Indexed Turkish Treasury bonds, but that would be too niche an audience and that’s not what we’re trying to do here.) So, in this article, we will apply the same rigor but give you the big-picture stuff.

Here's that big picture in a sentence: Inflation in Turkey has been spectacularly bad, it is still remarkably bad but better than before, but it seems to have plateaued at that “bad” level. We seasonality-adjusted more than 90 4-digit NACE code CPI components and constructed a seasonally-adjusted CPI series. The chart below shows the monthly percentage change in that. During the worst bouts of inflation, we saw more than 14 percent monthly increases, thankfully it did not stay there and for a while, it seems to have stabilized around 3 percent, which corresponds to a 41 percent year-over-year annualized increase. Not as bad as before, but still pretty bad.

The reason why we seasonally adjust everything in this article is to get rid of the seasonal factors that make it hard to do month-to-month comparisons and extract the underlying trend so we can extrapolate our findings into the future so that we can get a better understanding of the path CPI figures will likely take. But doing just that is usually not sufficient for that purpose because there are usually outliers that might affect the headline number but might not necessarily keep going in the same direction and magnitude. And that seems to be the case when we check the dispersion in the CPI basket. The chart below shows the year-over-year trajectories of various percentiles. (That is, it selects the product group that corresponds to that percentile each month and constructs an index and calculates YoY % changes. The 90th percentile selects the 9th product group that showed the most increase each month and the 10th percentile the 82nd out of 91 product groups.)

As it is abundantly clear, there are some product groups in the basket that had mind-boggling price increases in 2022, and there are some that had pretty “meh” paths. That’s why taking a look at the Trimmed CPI we calculated, once again using seasonally-adjusted data, might be more appropriate to get a clearer read on the underlying trend. It “trims” out every product group above the 85th percentile and below the 15th percentile each month.

And here it is in YoY terms:

It looks much better than the headline CPI figure in November, 84.39%, and it is not surprising that it does. Energy prices, which constitute a significant chunk of the CPI basket, were hugely affected by the Russia-Ukraine War, causing some outlier-level MoM changes especially early in the year. While it is certainly possible that there might be similar and significant shocks in 2023 (we learned to never rule out the possibility of something bad happening, ever since the pandemic), we think Trimmed CPI provides a much clearer picture regarding the overall inflation mechanics.

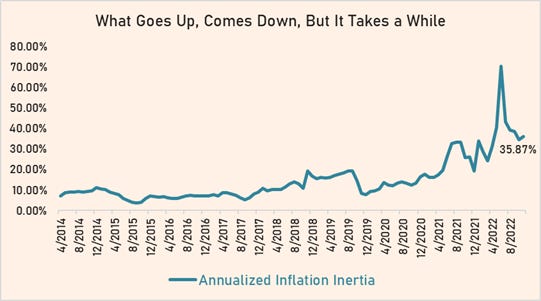

One other way to analyze those mechanics is to take a look at inflation inertia. It basically measures what would the inflation be if “nothing happened”. In some respects, it is obvious why this matters, but we care especially because it is a key figure in discussions about the competitiveness of an economy.

It essentially shows how much the currency of a country needs to depreciate to keep the real effective exchange rate constant. And it is a lower bound because there will be some passthrough from the depreciation itself. So, it is probably the most important inflation metric we track, because (though this example will sound absurd, bear with us) if an economy has an 80% CPI but 0% inflation inertia, that means policies aimed at reducing inflation can basically work instantaneously by removing the causes from the picture but if the inflation inertia is 80%, policymakers can do pretty much nothing in the short-term. (Or better put, whatever they do will take a long while to bring the inflation down.)

It is not a constant number, it changes constantly, so we treated it as such. The chart below shows the historical annualized inertial inflation figures.

The latest figure for November is 35.87% but the estimation is based on a rolling 12-month window, so we think the latest instantaneous figure is roughly 29 percent YoY. And this is, once again, clearly bad.

A lot of factors affect inertia like backward indexation and if the pricing behavior in that country is anchored or not. (Though if the inertia is 29%, it’s evidently unanchored.) So, if policymakers manage to do a good job with other factors affecting inflation itself or the global economic environment is favorable, inertia will come down over time as well, which is what happened after 2003. But as things stand, 29% is the mountain to be climbed.

The chart below shows the culmination of these three metrics: The CPI path they predict until the end of 2023, assuming that they stay constant until then.

The path of inflation inertia might look a bit rosy, and that’s because it is. Remember, we said it is where CPI would be if nothing happened. No Lira depreciation, no import price increases, nothing. But of course, “some” things will happen, instead of nothing. So, let’s briefly analyze what would those things be. (Briefly, because some of these things deserve a separate article that we will write in due time.)

1. Exchange Rate: We think CBRT has the means to keep the Lira on an extremely mild depreciation path, as portfolio flows, the current account, and bilateral relations with a host of countries are improving, and there has been a roughly 12 billion dollars increase in reserves, excluding swaps and Treasury cash, in the last 2 months. The question is, will they choose to do so. We think the answer is yes because the government apparently wants to lower the inflation as much as they can until the election while engaging in some election-spending and enacting some populist measures required to win the election, so they don’t want the impact of FX increasing the burden there, as it is abundantly clear from Minister Nebati’s latest speeches.

2. Energy prices: We think natural gas prices will remain high and oil prices will remain at their current levels. There is a chance of a small decline in domestic natural gas prices after the inauguration of the Black Sea natural gas but we think it’s not extremely likely. (We will talk about Black Sea gas in a separate article.)

3. Rents: We expect some impact from this as the cap on rent hikes will expire at the end of June and a new cheap mortgage loan package is a possibility, though we expect it to target first-time buyers and be small in scope.

4. Remember we mentioned some populist policies to be enacted? This is the big one. [AND WE HATE THIS.] It is strongly likely that a law allowing roughly 2 percent of the labor force to retire early will be passed in early next year with the support of both the opposition and the government, and some government officials mentioned a commercial loan package backed by the Credit Guarantee Fund might be in the cards to help firms weather this. This will have a relatively major impact both because of the loan package and the huge amount of retirement bonuses to be spent in a short amount of time. [Have we told you about how much we hate this? Better safe than sorry: WE HATE THIS, PASSIONATELY.] We plan to write further about this some other time.

5. Minimum Wage Hike: We expect the monthly net minimum wage to be increased to 8000 TL which would amount to an 88 percent increase year-over-year, though only 45 percent since the last hike in July. We forecast it to have a sizable impact as well. However, we have to make this distinction: It is not the wage hike itself that will have the impact. It’s just that it will allow firms to hike prices while having the wage hike as an excuse, as they already increased their profit margins beyond the level that can compensate for the wage hike. Because that’s what “unanchored pricing behavior” is: Firms not needing to think twice before increasing their prices.

As a result of these factors, we forecast the end-of-2023 Turkey CPI figure as 35 percent. We will let you know if any crucial changes occur in the elements of this analysis.

We would like to apologize for this article arriving a bit late due to some health issues. To make up for it, we will publish two more macro pieces this week. So, until then, have a great rest-of-the-week!